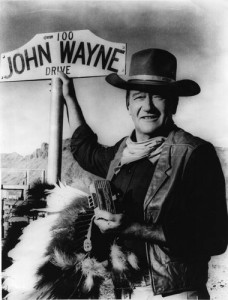

American actor John Wayne stands by the street sign honoring his name in Prescott, Ariz. The film star “was one of the defining Americans of the 20th century,” says critic John Powers.

Given all the heroes and soldiers he played over his half century in film, this year, it’s only fitting that John Wayne’s birthday should fall on Memorial Day.

Around the world he still enjoys steady popularity like no other long-deceased movie star. In 2003, over two decades after his death from cancer in 1979, he was listed on the Harris Poll’s top ten list of movie stars. Just two years before, a Gallup Poll voted him the top movie star of all time. He is a symbol — a touchstone — still used to define the American spirit, here and abroad.

The Duke was not an actor of great range, and would have been first to admit it. In the vast majority of his pictures, he played himself — and that was enough.

Before his first real break in “The Big Trail”(1930), he’d toiled in bit parts under the name Duke Morrison. (He’d earned the nickname “little Duke” as a boy in Glendale, California, because he was inseparable from his beloved Airedale, “Big Duke.”)

It’s no surprise the name “Duke” stuck: it was a far sight better than his given name, Marion (it’s no wonder he was so tough) — and unquestionably fitting for this tall, well-built young man who played football at USC before being indefinitely sidelined by a collarbone injury (legend has it that he did not receive the injury on the field, but rather while body surfing).

Still, once he was signed for “Trail,” the Fox studio wanted to give him a new name. Raoul Walsh, the film’s director, was reading a biography of Revolutionary War General “Mad Anthony” Wayne at the time, and suggested that moniker for Duke. The studio bosses felt “Anthony” sounded too Italian, so they agreed on “John” Wayne. Marion was not even in the room when they decided on his new handle. That’s Hollywood.

A newly minted John Wayne was then encouraged to take acting lessons to prepare for his first big part, but reportedly quit after just three sessions because the teacher told him he had no talent.

From there he adopted his signature style. Here’s Wayne’s account of how it happened: “When I started, I knew I was no actor and I went to work on this Wayne thing. It was as deliberate a projection as you’ll ever see. I figured I needed a gimmick, so I dreamed up the drawl, the squint, and a way of moving meant to suggest that I wasn’t looking for trouble but would just as soon throw a bottle at your head as not. I practiced in front of a mirror.”

He makes it all sound pretty simplistic, but of course, it was anything but. The creation of the Wayne persona was a stroke of brilliance right up there with Chaplin’s formulation of “the little tramp”.

But the magic spark — that special essence that comes off the screen and creates a star — had to be earned. Given that Wayne holds the record for the most starring roles by any film actor (142), it’s surprising how long it actually took him to break through. “The Big Trail” was not well received, and as a result, Wayne spent nearly a decade toiling in “B” Westerns.

When friend and future mentor John Ford decided to cast him as “The Ringo Kid” in “Stagecoach” (1939), stardom finally followed. Over the next thirty-five years, Wayne would rank in the top-ten list of box-office stars an astounding 25 times, a record until Clint Eastwood tied him years later.

So, what makes Wayne’s star still shine so brightly?

One consideration has to be his presence. He was a better actor than he gave himself credit for and three films in particular prove it: Ford’s “The Long Voyage Home” (1940) and “The Searchers” (1956), as well as Howard Hawks’ “Red River” (1948). In the sadly overlooked “Voyage,” Wayne stretches to play a gentle Swedish sailor, and nails the role. Though the other two parts hew closer to the Wayne cowboy hero mold, they still contain layers and depth that prove how capable of greatness the Duke was when given the right material.

Upon screening “Red River,” an astonished John Ford famously exclaimed: “I never knew the big son of a bitch could act.” Blunt but high praise from a master.

The second reason Wayne’s image has lasted is more practical: he stayed on the big screen longer than most all of his contemporaries. The Duke was still churning out movies long after the likes of Gary Cooper, Humphrey Bogart, Clark Gable, Tyrone Power and Spencer Tracy had passed away. Other stars that had survived either retired early (James Cagney, Cary Grant) or turned to television late in their careers (James Stewart, Henry Fonda). But the Duke just kept on going, beating a serious bout with cancer in 1964 that gave him nearly another decade and a half to work and sip his beloved tequila.

And what of the man himself?

Wayne’s outspoken, far-right political and social views did not help his legacy, particularly in the midst of the Vietnam War, when his blind patriotism and hawkish statements seemed simply out of touch. A rabid anti-Communist, he was a supporter of the Hollywood Blacklist. He later made foolish public comments that had a new generation branding him racist and homophobic. Not to apologize for him, but these were the utterances of a man who stubbornly resisted change – in politics, in film, and in social attitudes. And he was often too free in expressing his outmoded views.

To his credit, this supposed homophobe worked and became good friends with Rock Hudson, while fully aware of his orientation, and this supposed racist married three women of Hispanic origin. Also, his views moderated considerably toward the end of his life, in the wake of the Nixon resignation and Vietnam debacle. It was a surprise to many when Wayne attended the inauguration of Democratic President Jimmy Carter in 1977.

Politics aside, most of those who really knew him loved him. I was lucky enough to become friends with Claire Trevor in her later years; she was Wayne’s co-star in “Stagecoach” and 1954’s “The High and The Mighty” (Claire is perhaps best remembered for her Oscar-winning performance as a drunken floozy in 1948’s “Key Largo“).

She was extremely close to Duke Wayne for over three decades, and clearly adored him. One night she confided that underneath the macho image, he was actually a very sensitive man. I asked her to give me an example.

Claire led me into another room, opened a box of correspondence, and started rummaging. She finally found a piece of paper, and handed it to me. It was a poem Wayne had written — unsolicited — to one of Claire’s stepsons after some painful incident, the details of which I confess I no longer recall. Reading it, I was astonished by its wisdom, eloquence, and sensitivity. A poem from John Wayne: imagine what that might go for at auction.

The Duke’s filmography speaks for itself; on our site we’ve isolated thirteen Wayne films that we believe reach the pinnacle of greatness. We hope on this occasion you’ll check a few out either again or for the first time.

Back in 1969, John Wayne was asked how he’d like to be remembered. His response: ” I would like to be remembered, well . . . the Mexicans have a phrase, ‘Feo fuerte y formal’. Which means he was ugly, strong and had dignity.”

Well, Duke — two out of three ain’t bad.

Via Huffpost