June 11th marks the 30th anniversary of the passing of screen legend John Wayne. Most of the directors who made his classic films are of course long gone as well, so I was very pleased to sit down with Mark Rydell, director of The Cowboys (1972), the epic cattle drive saga most Western fans regard as Wayne’s last great starring role.

Rydell began directing theater in New York City in the early sixties, and went on to television and movies, including hits like The Rose (1979) and On Golden Pond (1981). We met at The Actors Studio in West Hollywood, where he and co-director Martin Landau continue to moderate acting classes.

MARK RYDELL: The fifties. I went through the Neighborhood Playhouse in 1949; I studied with Sanford Meisner for two years, then I was very fortunate to be on “As the World Turns” for many years, so I avoided a lot of the unemployment agony so many actors go through.

It’s true. When you’re a theater director in New York, and then you come to Hollywood to direct a picture, suddenly you’re in charge of all these crews; the lighting people, the sound, all these technical things. Something I’ll advise young directors to do is go to museums and study paintings. You know, how do you create a frame that’s filled with dramatic tension? You learn about composition…

I’m always interested in how painters “light” things.

Sure. Look at any Rembrandt painting; see where the light source is, how it affects the subject, where the shadows are. When you direct theater, your main tools are the actors and the script; when it comes to movies, you have to expand your judgment to the various aspects of visual presentation.

Though I get the sense not a lot of movie directors are coming out of theater anymore. People coming in seem to be mostly from commercials and music videos.

And you know what the problem is with those commercial guys? They only know how to keep it alive for thirty seconds. They’re very skilled, these directors—staggeringly brilliant and sophisticated visually—but I find they rarely understand the depth of written material. So many commercials today don’t even tell a story, or have anything to do with the product; they’re literally just thirty seconds of dazzling images… so you’ll associate the product with something you found viscerally exciting.

Rydell’s debut feature film, The Fox (1967), was based on a D.H. Lawrence story, and won the Golden Globe for Best Drama. His second film, The Rievers (1969), was adapted from the Pulitzer Prize-winning novel by William Faulkner.

That’s kind of unusual, starting a feature career with two prestige pieces. Most people have to start with trash.

I did plenty of trash. That was television: you’d get a script for something like “The Ben Casey Show” or “Dr. Kildare;” you read it, and you see it’s crap. So what do you do? You have to work. So you find something in the material that moves you, something private, and you let that private interest shape the rest of it, so by the time you’ve finished directing your “Gunsmoke” or whatever, you think it’s the best thing you’ve ever done.

I assume what generally moved you back then was working with the actors?

That’s probably my dominant skill. I think it’s a pleasure to work with actors; they’re so vulnerable, they’re so available, they’re so geared to do the right thing…

But being an actor yourself, you appreciate them because you know their process. I think a lot of directors regard actors like they’re space aliens. And I think it’s worse for men. It’s “cute” when women dedicate themselves to acting, but when a man does it… I think a lot of people see it as un-masculine.

Marlon Brando used to say that to me; that acting was a child’s game, and not for men. He was a very tough guy. Strong, sensitive, very competitive; an amazing actor—his ability to accept imaginary circumstances and behave within them was incomparable—but he was very unhappy. A sad, sad fellow.

And then there was John Wayne… How did you get involved in The Cowboys?

An agent walked in and put an unpublished novel on my desk. I sat down and read the first fifteen pages or so, and it was about this man who loses all his ranch hands to a gold rush. He’s got 1,500 head of cattle to get to market, and he walks into a schoolhouse. I knew I had a movie right there.

Did you have any particular affinity for Westerns?

I was from the Bronx; I’d never been on a horse in my life. I watched Westerns growing up, but I felt apart from them. It wasn’t my department. But doing all those “Gunsmoke” episodes—maybe a dozen or so—was a big help. We shot them in Thousand Oaks, which was really open country back then. Twenty minutes from L.A., and there wasn’t a telephone line in sight.

So I took that Cowboys manuscript to John Calley at Warner Bros., threw it on his desk, and said, “You’ve got 24 hours to make a decision on this before I go elsewhere.” He said, “Arrogant, Mark, aren’t you?” I said, “Absolutely. This is a big deal.” He called me an hour later, and said we had a deal.

So John Wayne wasn’t even involved yet?

No, and I didn’t want him; I wanted George C. Scott. But they had a deal with Wayne, and Calley said, “Let’s just go meet with him. He really wants to do it.” He was shooting in Mexico, so we got on the Warner Bros. jet…which I thought was terrific, but it was ultimately charged to my Cowboys budget. Nothing’s free!

I was absolutely stunned by John Wayne. I mean, he was the exact opposite of all my ideals—he was very right wing, one of the founders of the black list in the fifties—and I was this Jewish musician from the Bronx with pretty liberal views. So there I am sitting with him. He shook my hand—my hand disappeared inside his, it was so big—and he said, “I’d really appreciate it if you gave me the chance to play this part, sir.” I was completely seduced by him. I told him, “Let’s never talk about politics, let’s just talk art.”

And he was fabulous; the first guy on the set every morning, and the last guy to leave at night. This man I had loathed… I had disagreed with every position he’d ever taken, but I learned a lot from him, about determination, and commitment.

What I’ve read about his late career is that he surrounded himself with cronies, from the directors and writers on down. It sounds like that wasn’t the case here.

Nope. I had him alone. And he called me “Sir” for the whole picture! I was a kid, in my thirties, and he was a giant, a 6’ 5” walking icon. It was amazing. We shot it all around Santa Fe, and to walk into a restaurant there with John Wayne… everybody came over for autographs… and I never saw him turn away a single fan.

He certainly looks like he’s enjoying himself in the picture. So I guess, unlike Brando, he never tired of stardom. He really loved being John Wayne.

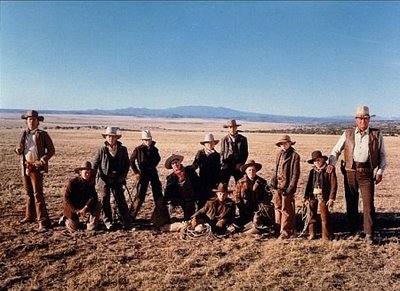

And he loved being with those kids. And they adored him as well; they climbed all over him like he was jungle jim. He also loved that I cast a bunch of people from The Actors Studio around him, like Roscoe Lee Browne and Bruce Dern. He was very keen to appear with them; he really wanted to show that he was as good an actor as they were.

Yeah, Roscoe Lee Browne is amazing in it. I can’t think of a Western that ever had a better role for a black actor. His presence, his voice… he was like Orson Welles.

I first directed Roscoe in a play called “Bohikee Creek” at The Actors Studio. He and Billy Gunn played these dirt poor clam diggers off the coast of South Carolina; for the whole play, they talked like, “We gone git dat boat, an’ den we gone do lahk…” Well, the reaction from the audience was tremendous, and the two of them came out afterwards to answer questions. When Roscoe began to speak in his own voice—these beautiful, melodious tones—people were just stunned. They couldn’t believe it.

So much was made at the time that Bruce Dern played the first villain to ever kill John Wayne in a movie. Is that actually true?

It wasn’t so much that he died, but that he got killed so far before the end. There’s still another whole act left to go.

The brutality of it is also pretty shocking, given that the tone of most of it is fairly benign. Then those bullet hits come… it’s like a scene out of Peckinpah.

Exactly. That’s what we wanted. That it comes like a slap in the face.

Also, when you think about that era—the early seventies—I’m sure a lot of John Wayne’s fans savored those moments in his movies when he kicked some hippie ass. I can just imagine all these tough guys going to The Cowboys… and sitting there in disbelief when this squirrelly, longhaired punk actually gunned down the Duke!

Bruce only half-jokingly said it ruined his career; that people just thought of him for years as the psycho who killed John Wayne.

Of course, psychos were already his stock in trade; he’d been doing it in those biker movies for years. I’m guessing The Cowboys was probably the first time a lot of mainstream America really noticed him. And he’s absolutely riveting; one of the greatest Western bad guys of all time I think. And he doesn’t even have that many scenes.

But he sure makes the most of them. That scene where he’s dunking the kid in the water… see, Bruce was very smart: he never got friendly with any of those kids. He was very cold to them, so of course they all felt intimidated by him. “Why doesn’t Bruce like me?” So when it came to that scene, where he threatens to drown the kid, or later, when he crumples the glasses—there’s not a lot of acting there; that boy was scared.

They say you should never work with children or animals. How hard is it keeping control over a herd of cattle and a cast full of kids?

The cattle drive was really quite complex. We had maybe twenty outriders, ready to come in and rescue somebody in case there was a problem. The kids really were herding those 1,500 head of cattle, and John Wayne insisted on doing everything himself; he had no stuntman. Even in the beginning, when he’s fighting that horse—that’s all him. All that tough riding; he did it all. He was an amazing guy; he just blew my mind. I consider it a major privilege that I spent those 102 days with him. And he was so pleased with the picture.

By Jon Zelazny, The Hollywood Interview

Read the full post at The Hollywood Interview blog.