John Wayne has been on people’s minds lately. Dick Cavett recently wrote a nostalgic New York Times piece about his lone meeting with Hollywood’s “Duke.” He also told of the meeting on the Dennis Miller Show.

Meanwhile, liberal author Gary Wills, presumably an expert because of his 1992 book John Wayne’s America; the Politics of Celebrity, was on another radio show loudly exhorting Wayne as a draft dodger during World War II. Oh, the hypocrisy of it all, Wills went on with glee that America’s biggest media patriot had shirked service during one of the nation’s most trying times.

Perhaps Cavett and Wills were both reacting to last years Harris Poll where amazingly Wayne was still ranked third amongst America’s favorite male film stars. Wayne is the only deceased actor on the list and the only one to have appeared in the top ten every year since the poll was started in 1994, despite the fact that he died in 1979.

Wayne once said, “It’s kind of sad when normal love of country makes you a super patriot.” That kind of honest sentiment that came across on film has helped the “Duke” maintain such a revered place in so many American hearts and minds.

The charges of Wayne being a “draft dodger” are not new and with a simple Google search one can find any number of far left types absolutely blowing their “peace and love” credentials over Wayne and his lack of service in World War II. The truth is far more complex and even “hidden in plain sight” than one would think.

Upon graduating from Glendale High School in 1925, Wayne applied to the U.S. Naval Academy at Annapolis, hoping to live out his dream of being a career Naval officer. He came close but was instead chosen the first alternate candidate.

By the start of World War II Wayne had been suffering for years from a badly torn shoulder muscle incurred in a body surfing accident that cost him his football scholarship at USC in 1927. He also had a bad back from performing his own stunts during ten years acting in “B” Westerns. Moreover, he suffered from a chronic ear infection, resulting from hours of underwater filming on Cecil B. De Mille’s Reap the Wild Wind in 1941. Had Wayne actually undergone a pre-induction physical, he might indeed have been classified 4-F.

According to Randy Roberts and James Olson’s top notch John Wayne American, as a married but separated father of four and thirty-four years old in 1942 Wayne was classified by the Selective Service as 3-A (deferred for family dependency). In 1944 as the U.S. Military feared a manpower shortage he was reclassified 1-A (draft eligible). There is no record that he disputed this reclassification but his employer, Republic Studios, did and requested he be given a 2-A classification (deferred in the national interest, i.e., war bond drives, visiting the troops, etc.). Selective Service records for World War II are spotty at best, many having been destroyed, but surviving records indicate these claims were filed “by another,” i.e. Republic Studio’s legal department. In fact, a letter from Republic Studios head Herbert Yates threatened to sue Wayne for breach of contract should he leave the studio for volunteer military service, though it is doubtful he would have carried through with the threat. But Wayne was indeed Republic’s biggest moneymaker during the war and that studio’s only “A” star at the time.

Yet, according to director John Ford’s grandson, in 1943 John Wayne tried to get a commission in the Marine Corps and get attached to Ford’s O.S.S. (the forerunner of the C.I.A.) Field Photographic Unit. In Pappy; the Life of John Ford, Dan Ford says emphatically “…that the billets were frozen in 1943. John (Ford) couldn’t get Wayne in as an enlisted man, much less an officer.”

For Duke; the Life and Image of John Wayne Ron Davis interviewed over seventy Wayne intimates including Jimmy Stewart, Douglas Fairbanks Jr., Harry Carry Jr., Robert Stack and Gene Autry, who all served during World War II. He never noted criticism of Wayne on the draft issue from any of them.

There is a letter from Wayne to Ford in May of 1942 in the John Ford Papers at Indiana State University quoted by Davis in which Wayne practically begs his mentor to find a way for him to join up: “Have you any suggestions on how I should get in? Can you get me assigned to your outfit, and if you could, would you want me? How about the Marines? You have Army and Navy men under you. Have you any Marines or how about a Seabee or what would you suggest or would you? No I’m not drunk. I just hate to ask for favors, but for Christ sake you can suggest can’t you? No kidding, coach who’ll I see.” No response by Ford has yet surfaced but these don’t sound like the words of a man shirking his duty. Wayne’s sometimes secretary at Republic, Catalina Lawrence, remembered writing letters to various military officials inquiring about possible service during this time period.

There has always been a suspicion that Ford refused to intercede on Wayne‘s behalf because he knew that with so many other male “A” stars in uniform that his friend would have an excellent chance of becoming a major star. Also, as great a director as Ford was he could often display a manipulative and sadistic side a mile wide. He might have refused to help in order to have something that he knew was important to the actor over Wayne’s head for the rest of his life.

Ford’s Field Photo Unit was no rear echelon cakewalk either, composed mainly of cameramen, sound men and editors with Ford as the boss. They were often right in the thick of things as they were on June 4, 1942 at the decisive naval battle at Midway where Ford himself was wounded by shrapnel. Two of Ford’s cameramen were killed during the war, Junius Stout and Arthur Meehan, both sons of well-known Hollywood cinematographers.

By 1943, with officer’s slots all filled, the only way Wayne could have gone into the service was as an army private; he had waited too long. Years later Wayne told Dan Ford that as a private, “I felt it would be a waste of time to spend two years picking up cigarette butts. I thought I could do more for the war effort by staying in Hollywood.” Almost all of the stars who served went in the armed forces knowing they would receive officer’s commissions. Most stars in the service found they were relegated to public relations duties out of harm’s way strictly for morale reasons. Adolph Hitler, a huge Clark Gable fan, reportedly put a bounty out for Gable’s capture Both Gable and Jimmy Stewart managed to cajole their way into combat, Gable in charge of a film crew aboard a B-17 and replacing wounded gunners more than once and Stewart flying twenty combat missions as the pilot of a B-24.

In 1993 Dan Ford, a decorated Vietnam combat officer, told Wayne biographer Davis, “It must have weighed heavily on him which way to go. But here was his chance and he knew it. He was an action leading man, there were a lot of roles for him to play. There was a lot of work in ”A” movies, and this was a guy who had made eighty “B” movies. He had finally moved up to the first rank. He was in the right spot at the right time with the right qualities and willing to work hard. Would I have done any different? The answer is hell no.”

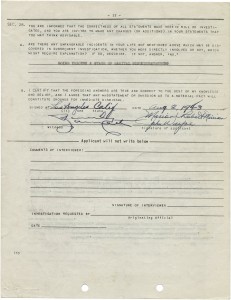

Then in 2003 the above document surfaced in a National Archives traveling exhibit that at the time stirred no great interest — John Wayne’s application to the O.S.S. On page twenty-three in a Los Angeles Times Magazine article dated September 21, 2003 Coming Soon: Living History On Exhibit are photos of two pages of at least twelve of Wayne’s August 2, 1943 application SA-1, page eleven marked in red pencil at the top “22087.” There is no doubt it is Wayne, he uses his birth name of Marion Robert Morrison, his middle name being changed to Mitchell after the birth of his younger brother Robert and his next of kin is listed as his then estranged wife Josephine Morrison with Mrs. John Wayne in parenthesis. Here for the first time is the first hard evidence that Wayne volunteered for potentially dangerous service with the equivalent of today’s C.I.A., and the papers are not out of someone’s attic, but official government documents. The only way Wayne’s application would have wound up in the National Archives is if it had actually been submitted to the O.S.S. The National Archives was created in 1934 to house and manage all federal records, including documents, photos and film, and now includes well over 4 billion items.

According to Roberts and Olson Wayne’s Republic Studios secretary remembered typing a letter in the spring of 1943 inquiring about openings in John Ford’s O.S.S. Photo Unit. A navy official responded in May that the navy and marine allotments for Ford’s unit were filled, but there was room for Wayne in the unit under the army’s allotment. Wayne secured the application and we now know he turned it in. Dan Ford recalled that Wayne told him he had been approved by O.S.S. commander William Donovan to join the Field Photographic Unit, but that the letter went to his estranged wife Josephine’s home and she never told him about it. The National Archives documents list her address as the same address as Wayne’s, the family home at 312 North Highland Avenue, Los Angeles. By the summer of 1943 Wayne had moved out and was staying at the famous Chateau Marmont Hotel on Sunset Boulevard, though he still visited his children at the Highland Avenue home. The dates and sequence of time seem to line up to support Wayne’s story, though additional information is needed to document the last part of the puzzle conclusively.

Wayne did do a USO tour in early 1944 in the Pacific and was asked by John Ford to keep his eyes out for O.S.S. commander William Donovan. The Pacific Theater commander General Douglas MacArthur was highly suspicious of the freewheeling O.S.S. and Donovan, who Ford was serving under, wanting to keep them from operating in his area of responsibility. Wayne is quoted in Dan Ford’s book that “I got to go places the average entertainer wouldn’t get to go… but I never did catch up with MacArthur. When I got back to the States I made my report, and they gave me a plaque saying I had served in the O.S.S. But it was a copperhead, something Jack (Ford) had set up. It didn’t mean anything.” When the certificate was sent to Ford’s home to give to Wayne, he didn’t even bother to pick it up and it remained amongst the director’s personal effects until his death.

That Wayne acknowledged that the recognition was meaningless, says a great deal, given the bloated egos of many actors, especially today, who are more than willing to exaggerate their own perceived accomplishments far beyond the credible. This also seems to raise doubt that there was any connection between Wayne’s O.S.S. application and the organization’s recognition of his “report” to William Donovan. If Wayne didn’t value the recognition in the first place, why bother to go through a formality to receive it.

On that same USO tour Wayne made it to dangerous combat zones where Japanese bombing runs and enemy infiltration occurred routinely. Not really a performer in the singing, dancing or comedy sense, mainly he just talked with regular grunt troops staying up drinking locally brewed “jungle juice” and swapping stories. He brought back vivid stories about these ordinary servicemen, “They’re where 130 degrees is a cool day, where they scrape flies off, where matches melt in their pockets and Jap daisy-cutter bombs take limbs off at the knee. What the guys down there need are letters and snap shots, cigars and lighters, phonograph needles and radios. They need the support and love of Americans back home.”

John Wayne was a patriot but not a hero, and he would have been the first to tell anyone that, though his courageous battle with cancer displayed the kind of understated heroics many could relate to. But if you watch some of Wayne’s best films his representation of a hero was certainly of great value and still has great value. He once explained the appeal of his image quite succinctly, “I define manhood simply; men should be tough, fair, and courageous, never petty, never looking for a fight, but never backing down from one.” So here’s one for the “Duke,” he may not have been a military hero, but we now have proof that he did actually volunteer for service in World War II.